November 13, 2018

American Ballet Theatre’s fall season at the Koch concluded about two weeks ago, so this post is belated. Nonetheless, I hope it provides some insight.

I attended two performances of the two-week run: the gala performance on Wednesday, October 17, and the Friday evening show two days later on October 19. The gala performance was a triple bill celebrating female choreographers, and featured ABT Studio Company and ABT Apprentices performing NYCB Principal Lauren Lovette’s Le Jeune, the world premiere of tapper extraordinaire Michelle Dorrance’s Dream within a Dream (deferred), and the Twyla Tharp classic In the Upper Room. The second two pieces were performed by the main company. The Friday evening show was also a triple bill: Artist in Residence Alexei Ratmansky’s Songs of Bukovina, the world premiere of Jessica Lang’s Garden Blue, and In the Upper Room, again—much to my delight.

I had seen Lovette’s piece for the Studio Company and Apprentices previously at the Hudson River Dance Festival over the summer, and had a hard time focusing in the lively outdoor setting. The gala was a good opportunity to revisit the piece, this time in a traditional proscenium setting. However, the work remained unremarkable. The music, by Eric Whitacre, is cinematic and dramatic, and the choreography doesn’t match—there is a disconnect between the two.

Dorrance’s piece featured ten dancers, five women and five men, engaging in social dancing, including lindy hop, and some tap dancing. Instead of a sparkling display of complex rhythms and intricate footwork, as Dorrance’s own company consistently presents, the audience received a novice display of an amalgam of dance forms. It looked and felt like a workshop for ballerinas to try their hand (and feet) at unfamiliar, uncomfortable styles—a healthy exercise, but not something appropriate for proscenium performance. A few dancers—James Whiteside, Cassandra Trenary, and Calvin Royal III—were confident, but most others looked unsure. The music was too soft in volume, and from where I was sitting, orchestra far house right, I could, for some reason, hear the stage manager calling each cue, which further dimmed the potential magic. The seventh and last movement of the piece finally picked up a bit, with the dancers clapping and stomping rhythms. Mr. Whiteside, as the ringleader, was strong. Overall, the work called to mind last year’s trite Fall for Dance collaboration between Sara Mearns and Honji Wang. In both, it felt too much as if the dancers were dabbling, and then performing prematurely, in a style and a specific, codified movement language that is not their own. I do, however, appreciate the dancers’, choreographers’, and company directors’ efforts to extend the traditional boundaries of ballet and take more risks. I hope that these innovative, “crossover” genre pieces improve over time as companies realize that they require a longer period of gestation.

************

In the Upper Room redeemed the evening for me—and was the reason for me to purchase a ticket to the Friday show, so I could see it a second time. This epic work is choreographed by Twyla Tharp, to the music of Philip Glass, costumed by Norma Kamali, and lit by Jennifer Tipton. Throughout the piece, which features a group of men and women in sneakers and another group in ballet/pointe shoes, stage smoke is pouring onto the stage and billowing out into the house. The fog it creates is even more striking in its effect when viewed from the fourth ring of the theater, where I was seated the second time I attended. It infuses the entirety of the theater, and creates the illusion that the dancers are magically emerging from and retreating into a smoky abyss, as they enter and exit the stage.

This theme of hiding and then revealing is mirrored in the costumes. Dancers remove various layers of clothing throughout to reveal red leotards, socks, pants, and skirts, hidden beneath their original black-and-white striped shirt and pant/skirt combination. Jack Anderson, a former New York Times critic, wrote in the review of the New York premiere of the work in 1987 at Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM),

In the New Testament book of Acts, Jesus’ disciples gather in an upper room, where they experience the presence of the Holy Spirit. Although there was nothing specifically religious about Ms. Tharp’s choreographic images, they did make one recall that, in the King James Version of the Bible, the Holy Spirit is compared with both “a rushing mighty wind” and to “cloven tongues like as of fire.”

“In the Upper Room” was a dance that rushed, shimmered and flamed. (Anderson)

I appreciate Mr. Anderson’s connection between this biblical “upper room,” the fiery characterization of the Holy Spirit, and Ms. Tharp’s choreography. I might also like to explore the connections among the biblical “upper room,” the invisibility but visible impact and power of the Holy Spirit, and the way Ms. Tharp works moments of concealing and revealing (invisibility and visibility) into the choreography through smoke and costuming.

The dancing in this ballet is classic Tharp and is characterized by rocking, loping, sweeping, scooping movements. There are moments of little head bobs and shoulder/arm shimmies for the sneaker women. Some of the shoulder shimmies become almost aggressive at times, as if the dancers are saying, “don’t mess with me, back off, stay back.”

Justin Peck surely must have seen this ballet. I can see its influence in his own sneaker ballets. I will need to see the piece a third time to analyze more clearly the relationship between the two choreographers’ works, but I did notice one contrasting quality: Mr. Peck’s port de bras (carriage and movement of the arms) often bursts outward from a high fifth position (in which both arms are raised and rounded above the head, almost making a picture frame around one’s face), while Ms. Tharp often scoops the arms from downward to up. Watching the piece, I couldn’t help but wonder if perhaps Ms. Tharp and Mr. Peck should be collaborating on the new Spielberg West Side Story remake.

The dancing, like the Glass score, is completely non-stop, for 39 minutes. The movement is highly aerobic, with lots of jumping and jogging. There are very little, perhaps no, moments of stillness. The music pulsates and follows a fairly quick, clipping tempo throughout. The dancers rarely have moments of rest: they are onstage moving, and then they are off, and then they are back on again. By the end of the piece you can see—though not as clearly from the upper balcony—that they are exhausted. Skylar Brandt and Cassandra Trenary, both Soloists with the Company, were standouts both nights I attended. There was a fullness, commitment, and ease to both of their sneaker-role performances that was particularly compelling.

The end of this ballet is cathartic, and I felt—twice—as if I had participated in some sort of communal, marathon event. I hope to see it again this spring on ABT’s Tharp triple-bill program so that I can specify what about the choreography itself is so thrilling.

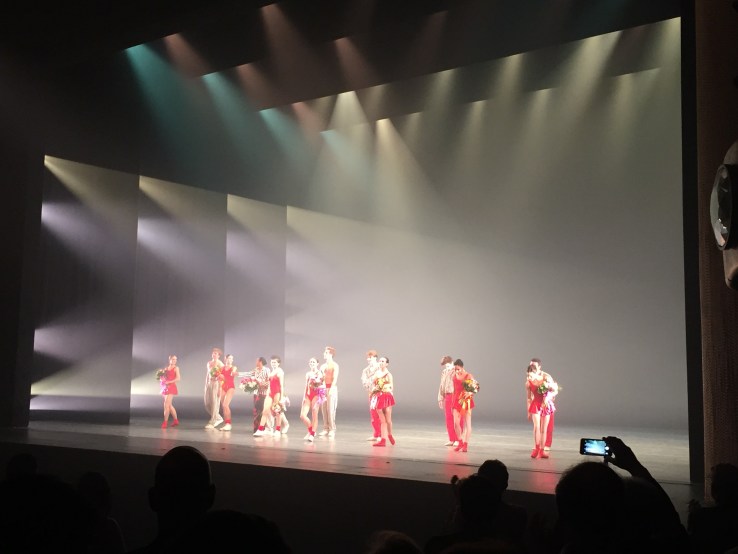

ABT dancers bowing after the gala performance of Twyla Tharp’s “In the Upper Room.”

************

Songs of Bukovina, which premiered last year, reminded me of Concerto DSCH which I saw recently on NYCB. Both of these Ratmansky ballets display village communities engaging in folk-inspired dancing. There are qualities and examples throughout Songs of Bukovina that will lead audiences to the image of villagers’ folk dancing: the women’s breezy, chiffon skirts are adorned with ribbons; there are instances of turned in and flexed feet; there are human gestures present (the lead man cups his ears to hear something); and the corps dancers, especially in “resting” positions, seem like real people. Ratmansky, here, displays his aptitude for corps formations. They unfold and become complex and shift constantly—but always resolve. This is a strength that I also observe and admire in Balanchine’s work. Both men share an Eastern European background.

In Songs of Bukovina, Catherine Hurlin, a young company member recently appointed to Soloist, danced remarkably. She is musical, quick, and vibrant. Her jumps are sparkling and, just like Ms. Brandt and Ms. Trenary in In the Upper Room, she exhibits a fullness of movement: she fleshes out the whole dance. The lead couple, Calvin Royal III and Christine Shevchenko, on whom the piece was created, looked quite nice. Mr. Royal was a bit shaky at first, but in one of the quicker, jumpier pas de deux sections, they were perfectly in sync, and shone.

Jessica Lang’s premiere, Garden Blue, was aesthetically and visually pleasing, in color palette, sets, and costumes, but did not make a strong choreographic impression. The three featured couples were each assigned a unitard color (yellow, red, or hot pink) and Hee Seo was outfitted in a white and green unitard. She is an outlier here and some kind of a force in the piece, but I am not sure what she represents or what her purpose is. She interacts with the others, but does not have a mate of her own. The backdrop was also color-blocked, complementing the costumes, and the stage was adorned with three wooden set pieces—one hanging in the air and the other two on the ground. They are manipulated, looking like abstract clam shells when placed on one of their sides, and then the prow of a ship on another. They were used as a hiding place, a platform, a shelter, and a resting place, in the moments I noticed. The bright group sections of dancing were more compelling that the individual pas de deuxs, which seemed to drag. The choreography did not stick with me, but the image of the stage, set, and dancers in costume does.

ABT dancers bowing after the world premiere of Jessica Lang’s “Garden Blue.”

Works Cited

Anderson, Jack. “The Dance: Twyla Tharp Troupe in Brooklyn.” New York Times, 5 Feb. 1987, p. C23.